Week 03: Introduction to graph representations and algorithms in the BGL

Table of contents

PoW: James Bond’s Sovereigns

- Goal: find the largest possible winnings that passenger \(p_{k}\) can collect regardless of how other passengers play

Splitting procedure of passengers

Passengers act in order

- \(p_{0}\) can pick

- left most \(s_{0}\) or right most \(s_{n-1}\)

One cycle, starts with \(p_{0}\), ends with \(p_{m-1}\)

- For \(p_{1}\)

- if \(s_{0}\) picked: choice between \({s_{1}, s_{n-1}}\)

- if \(s_{n-1}\) picked: choice between \({s_{0}, s_{n-2}}\)

The cycle starts with \(p_{0}\) again and repeats until no coins left.

First steps with BGL

Goal: Given a connected, weighted, undirected graph, compute the total weight of its minimum spanning tree and the distance from node 0 to a node furthest from it.

Input

- 1st line with no. vertices

nand no. edgesmof the graph - m consecutive lines, each with three integers representing a weighted edge

ep1 [space] ep2 [space] edge_weight- non-negative weights at most 1000

Output

- single line of

wthe sum of weights of all edges of a minimum spanning tree, anddthe distance from node0to a node furthest from it.w [space] d

Solution Technique

- this exercise serves as a gentle introduction to the boost graph library

- to find the MST one uses the Kruskal’s Algorithm, and to obtain the distance from node

0to a node furthest from it one can use Dijkstra’s Algorithm. - to iterate through the weighting map and subtract the sum of all weights one can use

std::accumulateand to find the maximum distancestd::max_element.

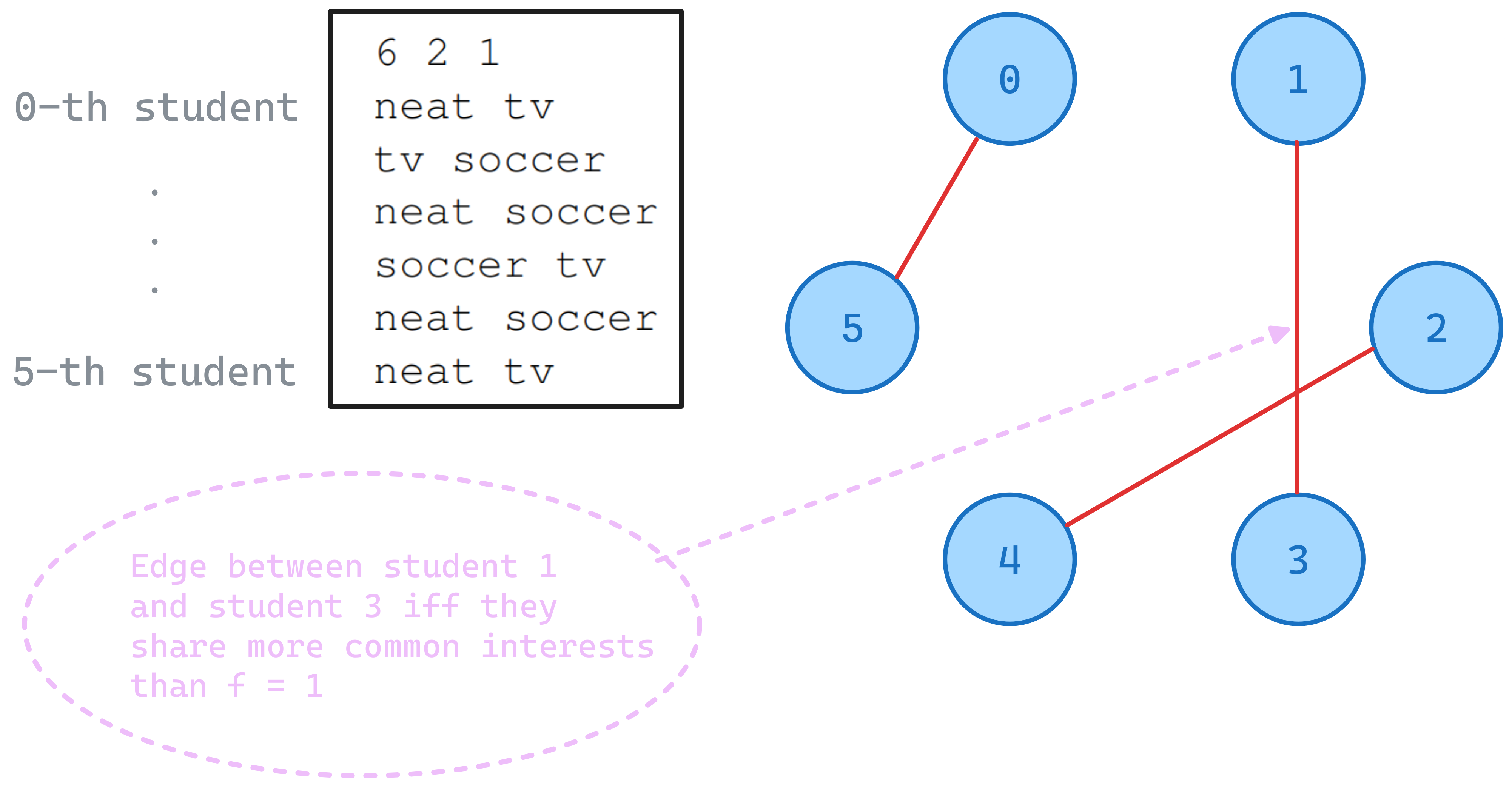

Buddy Selection

Input

- 1st line contains three integers

n [space] c [space] fnno. of students, an even numbercno. characteristics per studentsfcurrent maximum threshold of characteristics found over all pairs of students

- n lines describing characteristics of students, each line consists of

ccharacteristics (std::string) per student

Output

- single line determining if there is an assignment such that every pair shares more than

fcharacteristics.optimalnot optimal

Problem Modeling

We can use an unweighted, undirected graph graph to model the problem.

Every student is a vertex, and there is an edge between student u and v if and only if the number of common interests between them is strictly larger than the threshold f to be compared with.

An assignment for all students without leaving anyone alone is always possible because we have a one-to-one matching between students and the total number of students n is guaranteed to be an even number. A valid assignment \(M\) is a set of edges where each vertex is contained in exactly one edge. An example of such matching \(M = \{ \{0, 5\}, \{1, 3\}, \{2, 4\} \}\) is shown below.

Solution Technique

An essential step for the graph construction consists of checking no. common interests between students, for this we need to perform pairwise comparisons between every student i and j. To do this efficiently, we can employ sliding window technique on the sorted container that contains students interests.

We notice that assignments \(M\) are valid matching in graph problems and we can apply Edmond’s Algorithm on it.

Ant Challenge

Input

- 1st line of

n [space] e [space] s [space] a [space] b- no. trees

- no. edges

- no. species

- index of start tree

- index of end tree

- e consecutive lines of

u [space] v [space] w₀ [...] wₛ₋₁describing edges and cost for each species - 1 line of

h₀ [...] hₛ₋₁location of hives of species

Output

single line containing total cost on the optimal route fulfilling the private network constraint

Problem Modeling

The graph construction for the undirected, weighted graph \(G = (V, E)\) is defined by the task already. By task description, the graph itself represents a forest, with vertices being the trees and an edge is established between two trees if there is a path that connects them.

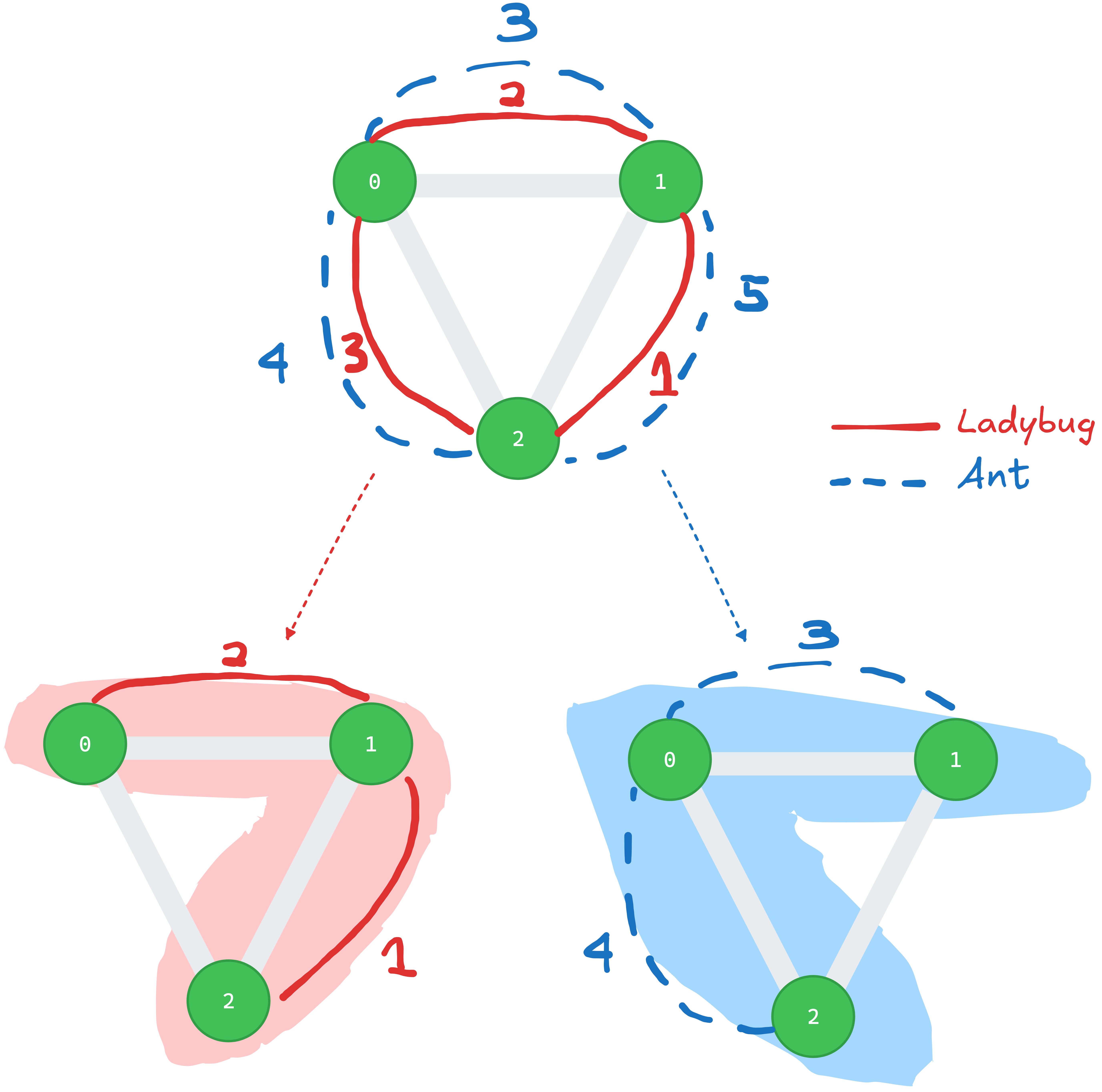

Construction of Subgraphs

The concept of a “private network” is introduced and leads to subgraphs \(G_{i} := (V_i, E_i), i \in \{0, ..., s-1\}, V_i = V, E_i ⊆ E\) one can construct from \(G\), where \(s\) is an integer number denoting the number of species.

For a species \(i\), one can construct the “private network” with a greedy algorithm where one starts from some node (hive of the species) with index h[i]. At each iteration, some node \(q\) from the set of unvisited neighboring nodes of the current node \(p\) will be visted, such that \(\{ p, q \}\) has the lowest weight. The iteration ends until \(\lvert V_i \rvert = \lvert V \rvert\), when all vertices are covered in the subgraph.

We notice that it is describing Prim’s algorithm for finding the minimum spanning tree (MST). Since all weights are unique, we can also use Kruskal’s algorithm to find the MST, which is more suitable for sparse graphs.

Construction of the Shortest Path

The shortest path algorithm should run on the union of subgraphs \(⋃_{i} G_{i}\), where the weights on the edges are chosen from the minimum from all possible edge values. One can see that the found shortest path should be some set of edges fulfulling \(P ⊆ ⋃_{i} E_{i}\)

For every edge there are s possible weights, but not all of them can be used! Only those that belong to some edge in some \(G_{i}\) can be chosen. Using the minimum out of all possible weights on an edge blindly is wrong.

In the following example, we see that the edge \(\{0,2\}\) is not part of the MST of the ladybug species. Consider the situation, where a = 0 and b = 2, then the shortest path that fulfills the “private network” requirements should be \(P = \{ \{0, 1\}, \{ 1, 2 \} \}\), and the total sum of such path is 3. Note that the following edge belongs to the union of the MST edges too. \(\{ 0, 2\} ⊆ ⋃_{i} E_{i}\), and if looking at all possible weights on it, we see that ladybugs need only 3 unit time, while the ants need 4 unit time. However, it cannot get the weight of 3 from ladybug species, because it is not part of the MST of ladybug.

Solution Technique

The solution process boils down to

- Construct subgraphs \(G_{i}\)

- Construct the union of subgraphs \(⋃_{i} G_{i}\) with best weights

- Run Dijkstra on the union of subgraphs with best weights

To construct subgraphs \(G_{i}\), which boils down to just constructing \(E_{i}\), we iterate through all species \(i \in \{0,..., s-1\}\), retrieve the weights of the current species from a prestored weight matrix, and find the MST with the Kruskal’s Algorithm. At every iteration, we also compare the cost of the edges that belong to the MST with previous values in order to keep track of the best weights.

During the construction of subgraphs, we stored the best weights for the MST edges in a std::map<edge_desc, int> that we can now use for the construction of the union of subgraphs with best weights by iterating through it.

After \(⋃_{i} G_{i}\) is constructed using edges of type edge_desc from the map, and the best weights after all iterations, we can easily find the optimal transport cost from a to b with Dijkstra’s Algorithm.

Important Bridges

Goal: Given a fully connected, unweighted, undirected graph, find the set of edges (bridges) that consists of edges that fulfill the definition of “critical bridges”.

Input

- 1st line of

n [space] mnno. islandsmno. bridges

- m lines of

e₁ [space] e₂- each describes indices of two islands that a bridge connects

Output

- 1st line outputs the no. of critical bridges

k - k lines of

e₁ [space] e₂containing the island indices that the critical bridge connects (lexicographic order)

Problem Modeling

From the problem statement we see that we are guaranteed to obtain a fully connected graph that consists of islands as vertices and bridges as edges that connect the islands. Since bridges are bidirectional and there are no weights to consider with, we can use an unweighted, undirected graph graph to model the problem.

Identify Critical Bridges

By definition, we classify an edge as a critical bridge, as long as the act of removing the edge from the graph \(G\) causes the graph to be not fully connected anymore.

Putting the connectivity of the graph into the context that we are operating on an unweighted, undirected graph, the concept of biconnected components shall ring a bell.

Below is an example taken from BGL documentation. It depicts a fully connected graph and there are 4 biconnected components found on the graph. We notice that the biconnected component with index 3 consists of only the vertices \(A\) and \(G\). More importantly, the edge \(\{ A, G\}\) fufills the property of a critical bridge.

![]()